In June, PM Justin Trudeau announced that Canada is increasing international funding for women and children’s health to $1.4 billion annually, starting in 2023. The ten-year commitment renews Canada’s current contribution to reproductive, maternal, newborn and children’s health to 2030 and is aimed at addressing critical gaps in sexual and reproductive health and rights (SRHR).

Made at the Women Deliver 2019 Conference in Vancouver, the new funding announcement maintains Canada’s leadership in advancing women and children’s health and rights, which started back in 2010 with the Muskoka Initiative on Maternal, Newborn and Child Health (MNCH). Led by then-Prime Minister Stephen Harper, the initiative saw G8 leaders commit $7.3 billion over years to MNCH, with Canada contributing $1.1 billion.

But what does that mean for partner countries abroad?

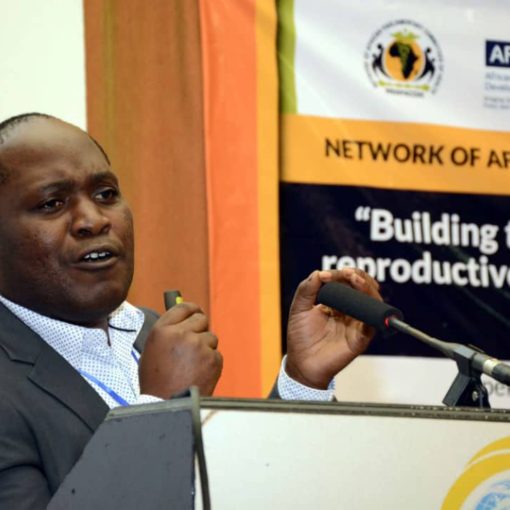

“One of the biggest contributions is capacity building,” says Nowadia Chipalo, our field administrative and logistics assistant in Tanzania. “At Mama na Mtoto, we have conducted several clinical simulation and leadership training workshops to community health workers and facility staff.”

Chipalo has worked with different development organizations over the past five years. Before Mama na Mtoto, she worked with a project implemented by Plan International Tanzania that aimed to eliminate child labour in mining areas and send children to school. She saw kids equipped with school supplies and their parents investing in health, education and income generating activities.

Although Canada is considered a global leader for contributions to MNCH, its work is not possible without reciprocating contributions from local teams and communities. They provide expertise that is essential to successful implementation.

“We teach our Canadian colleagues about Tanzanian life and advise on how to implement work in the Tanzanian context,” says Chipalo. “As well, we help introduce the project to communities through village orientations. We create interest in our project’s work by having communities involved early on.”

The range in expertise provided by both Tanzanian and Canadian partners allows for a comprehensive approach to improve not only the quality of clinical MNCH services but also the access to these services. For example, the importance of MNCH services does not typically align with traditional beliefs and values of the Sukuma, a large ethnic group in Tanzania.

“A woman cannot decide for herself to attend an antenatal clinic without permission from her husband. Many women give birth at home because their husbands feel that doctors that visit homes and practice traditional medicine are sufficient. This increases the risk of maternal and perinatal death,” says Chipalo. “Being able to implement development changes can be difficult with a community as it depends on its willingness to adopt changes.”

Thanks to the collaborative efforts of our partners and community health workers, we have seen progress in promoting male engagement in MNCH. Earlier this month, our local community engagement team saw twenty husbands accompanying their wives for their antenatal appointments at the Mwawile village dispensary in one day.

Such strides make Nowadia optimistic about the improvements of women and child health.

“The next step is to ensure that maternal and perinatal death is totally eliminated in Tanzania.”